Theme: Older People, through the Yorkshire & Humber Palliative Care Research Network

Care towards end of life is insufficient and inequitable

Over 500,000 people die each year. We know that the care they receive in their last months, weeks and days of life is not enough; those who die and their families simply do not get enough care and support.

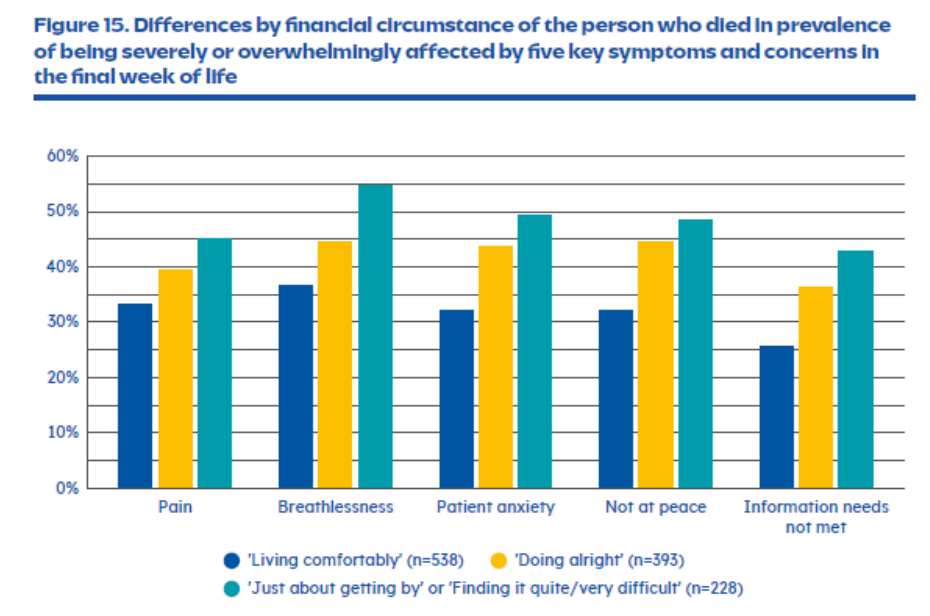

A recent survey showed that almost half (n=572, 48.5%) of those reporting the death of a family member were unhappy with one or more aspect(s) of care because it was lacking or insufficient. In addition, care towards the end of life is inequitable, with – for instance – those in poorer financial circumstances have higher levels of symptoms and other concerns, as this figure shows:

Figure from: Johansson T, Pask S, Goodrich J, Budd L, Okamoto I, Kumar R, Laidlaw L, Ghiglieri C, Woodhead A, Chambers RL, Davies JM, Bone AE, Higginson IJ, Barclay S, Murtagh FEM, Sleeman KE (King’s College London, Cicely Saunders Institute; Hull York Medical School at the University of Hull; and University of Cambridge, UK). Time to care: Findings from a nationally representative survey of experiences at the end of life in England and Wales. Research report. London (UK): Marie Curie. (September 2024) mariecurie.org.uk/ policy/better-end-life-report

Addressing inequities through research

We examined existing evidence to better understand the factors contributing to inequities in pain care, specifically for people with life-threatening diseases and serious mental illness, who have the poorest outcomes of all. Evidence showed that individuals with schizophrenia received significantly less analgesia than those without serious mental illness, despite allowing for other differences.

Barriers to optimal pain management included patient factors (such as difficulties in pain expression, behavioural symptoms), clinician factors (such as diagnostic overshadowing, stigma), and systemic issues (such as fragmented care, and restrictive prescribing practices).

However, our main conclusion was that there is a striking lack of research on pain assessment and management for people with life-threatening diseases and serious mental illness. We are taking forward new projects to address this lack of evidence.

Access to palliative and end of life care

Work from the East of England ARC demonstrates persistent concerns about inequity in access to palliative and end of life care. Inequities in access range across diagnosis (with access for those with cancer being much more readily available), and with the oldest old, ethnic minorities and those living in rural or deprived areas being under-represented in hospice and palliative care populations. Socio-economic status has less often been studied; evidence on this is sparse.

Socio-economic status and specialist palliative care

We wanted to discover whether there was a difference in outcomes across areas of different deprivation status for those receiving specialist palliative care and so undertook a secondary analysis of routinely-collected clinical outcomes data from all people cared for by one large service. This service extends across several very socio-economically diverse areas of South-East London.

We identified 8,638 episodes of community-based palliative care received by 6,808 people, over three years. The people receiving this care came from areas widely distributed across the deprivation deciles. They had a mean age 76 years (SD +/-15); were 53.7% female; 72.6% of white ethnicity; and 57.8% with a primary diagnosis of cancer. The proportion with improved symptoms after care was uniformly high, with no different across deprivation deciles. For those receiving specialist palliative care, in this service at least, there was therefore no evidence of a gap in palliative care-related outcomes for people from areas of different socio-economic status.

More research needed!

It is often easy to say ‘more research is needed’; inequities need to be addressed and rectified, not endlessly described. But it is also true to say that we often do not know why the inequities exist, and without this knowledge, we cannot make the required policy and clinical changes. Therefore, we have several ongoing and new projects to identify the reasons for inequities in care clearly and then make recommendations for change. Watch this space!