by Kristian Hudson – Implementation Specialist

I had the pleasure of interviewing Robyn Clay-Williams, a Professor of Human factors (see the full interview here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6d3LQzArHug). What she told me about de-implementation and patient safety was eye opening. Robyn explained that the more you can simplify and take things out of a system, the safer that system will be in the presence of change or complex problems. The more complex a system is, the more likely it is to fail and do so in an unexpected way. So the more we can de-implement within our health systems the better off those systems will be. A simpler system, means a more resilient system and a system which is more resilient in the face of any unforeseen events.

This approach tends to be accepted theoretically but trying to get people to accept it in practice is very difficult. This is something the Yorkshire Quality and Safety Research group are grappling with. In our YHARC blog of 8th September 2023, Qandeel Shah talks about de-implementation in mental healthcare settings. The de-cluttering (safely) for Safety theme in the NIHR YH Patient Safety Research Collaboration are also doing work to identify low value safety practices and to evaluate de-implementation interventions. Rebecca Lawton, YH ARC Improvement Science Theme Lead agrees with Robyn – ‘stopping doing things (especially when these are done ‘in the name of safety’) is difficult and anxiety provoking. We need to learn more about how to do this effectively’. People still have an understanding of safety from the 2000’s. They tend to think of unsafe events being the result of a cascade of errors. This is sometimes referred to as the ‘Swiss cheese model’ where there are holes in the different layers of a system and you get a cascade of errors through the holes leading to a significant adverse event at the end. The way many of us try to stop that happening is we put barriers in the different levels to stop the cascade from happening. However, we now know that that is not how systems work. They don’t fail in a linear way like that. Systems fail in unexpected and complex ways. The more barriers we put in the system, the more complex it is and the more likely it is to fail in an unexpected way.

Robyn gave me an example of this from aviation. On 24 March 2015, Germanwings Flight 9525 crashed 100km north-west of Nice in the French Alps, killing all 150 occupants. This was due to suicide by the co-pilot. The rest of the crew couldn’t get in to stop him because of the locks put on the doors after 9/11. These were designed to stop a terrorist getting in. So based on a previous unforeseen event, a barrier was put in place. This barrier eventually had dire consequences as it meant there was no way for the crew to respond to the new, unexpected event of the co-pilot deciding to crash the plane. The application of linear thinking to a previous complex scenario within a complex system would likely have stopped a potential terrorist but also led to an additional unforeseen problem and event down the line.

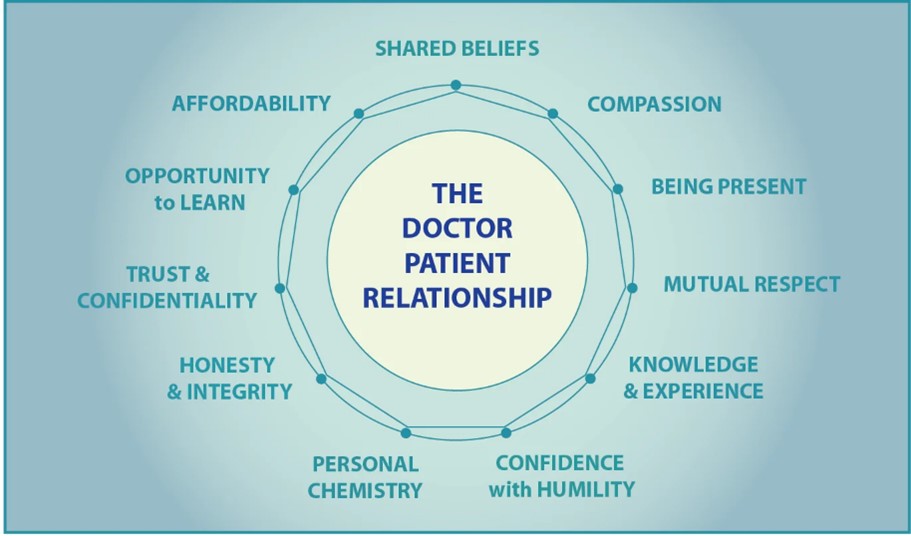

Our health systems are the same. We constantly put lots of layers in to stop things that happened retrospectively in the past. This may well stop the retrospective problem from happening again, but there are then lots of inadvertent consequences of other things that happen. For instance, we put in place many barriers to prevent problems around patient safety but this can lead to a decrease in the quality of patient care. A key tenet of healthcare is that healthcare professionals are supposed to provide patients with care but if they become so busy that all they do is follow processes they are not able to provide that one-on-one provision of care that is really at the core of what good healthcare is all about. The doctor-patient or nurse-patient relationship goes out of the window.

As Robyn explained, this is seemingly the case within hospital emergency departments. Ideally in a very complex system such as an emergency department you would use goal-oriented processes where you agree what the goal is i.e. to care for the patient, but also allow some degree of flexibility in how that is achieved depending on the situation and on the needs of the patient. This extra flex increases the chance of the healthcare practitioner successfully providing the best care possible to the patient. In a process-oriented system, like we are seeing in our current health care systems there are many, many guidelines, and an assumption that we already know what the goal is in regards to the patient. If healthcare staff want to achieve this pre-determined patient goal they must follow a specific process or guideline. It’s linear and logical. You just have to follow the list of steps. But when people start following steps they lose sight of the big picture. They lose sight of the ‘whole care interaction’. In our hospital emergency departments staff are just following processes and a lot of the processes are around the IT systems and to do with computer processes. This means the staff are spending more time on the computer, ticking boxes and making sure everything is being complied with, than they are with the patient which has a direct impact on the amount of time they are able to provide direct patient holistic care. This doesn’t just affect the patient, it also affects the healthcare professional who tends to feel burnt out, experience less joy and fulfilment at work and starts wondering why they are even in this particular job. It also hits on equity as not every patient who walks through the door will ‘fit’ the guideline already set out for treatment.

That brings me to implementation which also takes place in complex systems. We are constantly implementing at rocket speed into health systems which have very little absorptive capacity to implement anything new. We should probably be learning how to create some slack in the system so the healthcare staff can respond to complex implementation problems as they arise. We could do this by de-implementing checklists, processes and activities that no longer or never did service the patients. If we are to sustain and bolster our health systems, we may need to change how we think about implementation and patient safety.