by Kristian Hudson

Kristian Hudson is an implementation specialist with the Yorkshire & Humber Improvement Academy working with researchers and practitioners across the Yorkshire & Humber Applied Research Collaboration.

In Part 1 of this blog series I talked about some of my learnings as an implementation specialist. I found that there were limits to how far implementation science could help us understand ‘how to’ implement. I decided to go on a journey to find out and started interviewing implementation experts on my podcast Essential Implementation last year – https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCZu-S0m8tgInP9p6yOcuB-A. In this podcast I will share some of what they said.

I interviewed:

Laura Damschroder an international leader in advancing the science of implementation and lead author of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR), one of the most widely cited papers in implementation science

Michael McCooe an Intensive Care Unit consultant, who has been working with COVID patients during the pandemic in the Bradford Royal Infirmary in Yorkshire, England, UK, and he is also the Clinical Director of the Yorkshire & Humber Improvement Academy.

Ioan Fazey a Professor of Social Dimensions of Environmental change based at the University of York who has written a seminal paper on the implementation of solutions to climate change “Ten essentials for action-oriented and second order energy transitions, transformations and climate change research” https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2214629617304413

David Melia a registered nurse with 37 years experience, currently the executive nurse and deputy chief exec for Mid Yorkshire Hospitals NHS Trust.

Dr Elizabeth Taylor-Buck and Amanda Lane who implemented a patient reported outcome measure known as ReQoL into 80% of NHS Trusts over 4 years. ReQoL is also now being used in Holland, Sweden, China, India, Australia, Canada and the USA.

Dr Ali Cracknell, a Consultant in medicine for older people at Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, UK and associate medical director for quality improvement. Ali was fundamental in the implementation of ‘safety huddles’ a patient safety initiative across 136 hospital wards.

Jane Lewis and Bianca Albers from the Centre for Evidence and Implementation (CEI), an implementation intermediary organisation. CEI helps policy makers, governments, practitioners, program providers, organisation leaders and funders obtain better outcomes.

Alison Metz who directs the National Implementation Research Network at the University of North Carolina. For many years Alison and her team have been trying to use implementation science in the best way possible to improve outcomes in the areas of education, maternal and child health, early childhood, and child welfare.Deon Simpson a Service Improvement Specialist at Dartington Service Design Lab. Dartington have developed an approach known as Rapid-cycle Design and Testing. This is a method produced and tested by the where Deon works as. I saw Deon talking about this at an implementation science conference. I felt this approach is another important piece in helping us implement well so I got in touch and asked her for an interview.

The first thing I learnt was that implementation science has tended to focus on the problem but not the practice of implementation

After my interview with Ioan Fazey, Professor of Social Dimensions of Environmental Change at the University of York, the reason for the ‘science to practice’ gap in implementation became much clearer. The majority of the implementation science literature comes from a place of problem analysis, which, as Ioan Fazey explained on the podcast, is very different to the practical knowledge needed to know ‘how to’ implement. Implementation science comes predominantly from universities.

Many of these institutions were deliberately set up to be separate from ‘the problem’ so they could analyse it. They are often hundreds of years old and very, very good at analysing ‘the problem’. Imagine implementation was a bicycle. The academic knowledge generated by universities can tell us the reason this bike exists, what this bike looks like, what each part of the bike does, how to build the bike and details such as how much the bike weighs; but it cannot tell us how to ride the bike. Not really anyway. It might say ‘get on and pedal’ just like you might tell a nurse to ‘create an implementation team’ but it is only from riding the bike and falling off, or being a nurse and creating an implementation team, that individuals in these two situations actually learn ‘how to’.

To ride a bike requires more than academic knowledge. It requires certain motor skills, muscle strength, muscle memory, balance and aerobic fitness. As you are harnessing these skills and riding the bike around you learn to look out for objects on the road and potential hazards. You get more confident and may well start riding faster. It is a skill that can only come from trying and learning. The same goes for the nurse tasked with implementing something on his ward. He will learn, over time, ‘how to’ in a way which implementation science and academic knowledge cannot offer him. To highlight the extent of this problem, Ioan Fazey did a back of the envelope calculation in 2019 on 5000 papers on climate change which had been produced that year. He skimmed through and found that roughly 90% were problem analysis, 8% were about solutions creation, only about 2% were about implementation.

I know I’ve laboured this point but it is a really important one. Riding is the only way to really learn to ride a bike and implementing is the only real way to learn ‘how to’ implement. So what does that mean for implementation science? Well it might mean that implementation science needs to develop further its relationship to the practical so the science can provide more support to people trying to learn ‘how to’.

This support will require implementation scientists and researchers to develop strong relationships with practitioners and support them so they can collectively generate that much needed ‘how to’ knowledge. Iaon gave a great example of a project by the Soil Association where each site had an academic and a farmer. The aim of the project was to yield more crops from the soil. But rather than come up with a solution and give that solution to the farmer, the role of the researcher was to show the farmer how to do their own and better soil experiments and learn how to get more yields themselves.

What might combining implementation science with a more practical approach look like?

I first got an indication of how I could help people learn ‘how to’ implement interventions when I interviewed Laura Damschroder who created one the most cited implementation frameworks in the world – the consolidated framework for implementation research (CFIR). It lists 38 constructs across 5 domains which can act as potential barriers and facilitators when someone is trying to implement something.

In her interview she explained how she can apply the CFIR to a setting and discover what is blocking successful implementation the most. She might find that a lack of communication between team members is the biggest barrier. She can then come up with an implementation strategy to overcome this. But it will be the people and teams in that setting that will be tasked with carrying out that strategy and to do this they will have to come up with a whole range of micro-strategies to ensure better inter-team communication. It is these micro-strategies and the people in the setting that actually drive change. These people contain a knowledge that isn’t accessible elsewhere.

So implementation isn’t just about implementing ‘once and for all’. It is also about empowering teams to keep ‘implementing’ indefinitely and that means continually optimising the intervention in the face of an ever-changing environment and demands. Without this your intervention is a lot less likely to be sustained. Laura therefore embeds herself within the settings she is working with and trains receptive teams in how to overcome problems to implementation as they arise. In her interview she referred to the Dynamic Sustainability Framework.

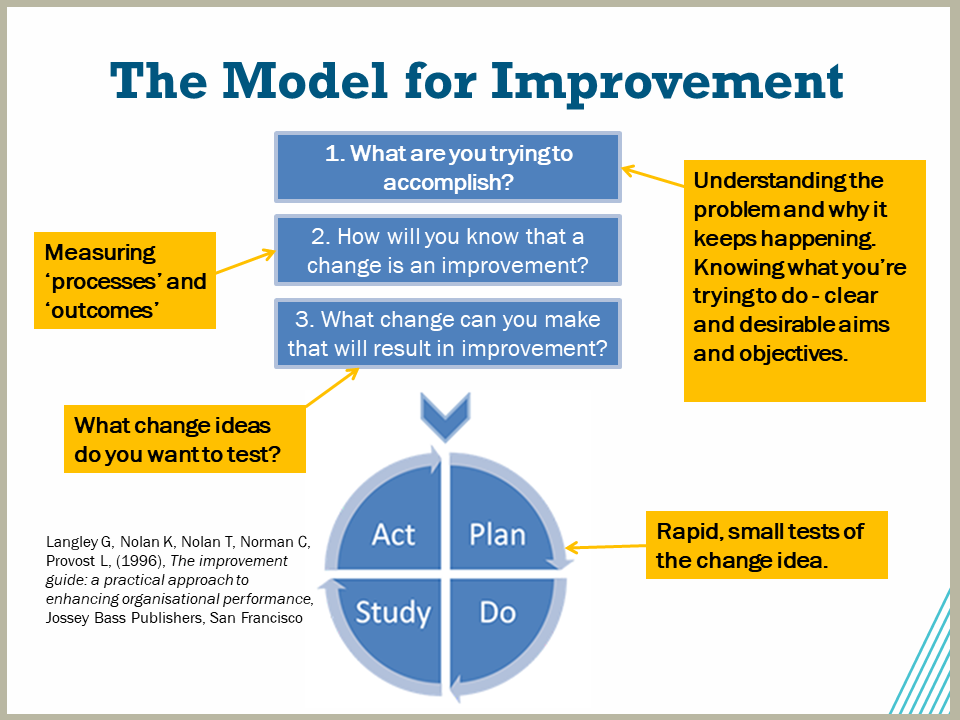

The Dynamic Sustainability Framework (DSF) is an implementation framework which puts forward the idea of teams continuing to learn, problem solve and adapt their intervention after initial implementation (Chambers, Glasgow, & Stange, 2013). Laura has adapted this approach into how she works with teams and will use improvement science techniques such as a Plan, Do, Study Act, cycles to train teams to continually optimise their intervention over time. This is a great example of how an implementation science framework can help teams to keep a good fit between the intervention and their constantly changing context. The expectation going forward starts to be about ongoing improvement as opposed to diminishing outcomes over time – goodbye voltage drop!

Implementation practitioners are the ones to make implementation science practical

If you look at all of the implementation science frameworks, it is rare to see a paper published where one of these has been truly integrated and used in a practical way to improve implementation outcomes. Take the Knowledge to Action Framework as an example. In the Field et al. (2014) systematic review of using the Knowledge to Action Framework in practice, the authors found 146 studies that reported using the KTA Framework but out of these only ten (7%) used it in an integrated way i.e. in a way that meant it was integral to the design, delivery and evaluation of their implementation activities, as it was designed to be used. The issue with this is that if implementation frameworks are not used with fidelity they are likely to be less effective in practice (Taylor et al., 2014).

Perhaps to understand and use implementation frameworks and approaches fully and with fidelity requires a specialist who understands them. It is unlikely a clinician or frontline worker would have time to scour the scientific literature for knowledge which might be able to help solve a problem (such as is required by the Knowledge to Action Framework), then adapt it and look for barriers.

The frameworks are built by academics and can tend to assume that knowledge and solutions must come from outside the practitioner context. The Knowledge to Action Framework satisfies a lot of academic requirements. It has been heavily researched, it is great for referencing on papers, it tries to get practitioners to follow a very academic process but going through the steps can take years and very often practitioners need to solve problems rapidly e.g. to get pneumonia deaths down by next week. And there are still implementation scientists who believe that primarily, the context should be bent to fit the intervention rather than the other way round. But in actual fact when one allows for adaptation, outcomes tend to be a lot better (more on this later).

This is probably why after 20 years as an implementation scientist and thinking about what really matters when it comes to implementation Allison Metz, a long-standing expert in implementation science feels that relationships might not only moderate implementation strategies but may well be more important than them. So another key part of the ‘how to’ question is how to form effective relationships. As Alison explained, relationship building is a core competency of any serious implementer and she has eloquently laid this out in a recent publication discussing the role of implementation support practitioners (Metz, Louison, Burke, Albers, & Ward, 2020).

Implementation support practitioners (also known as intermediaries, improvement advisors, technical assistance providers, facilitators, consultants, mentors, and implementation specialists) use their experience and knowledge to support organisations, leaders and staff to ensure evidenced based practices are implemented well and sustained into the future. They have extensive knowledge of the implementation literature as well as direct experience of supporting real world implementation. They may be embedded within the delivery system they are helping or outside of it.

It is vital they have the ability to activate implementation-relevant knowledge, skills and attitudes, so that they can be operationalised and applied in the target context. For a good logic model of this process see Bianca Albers paper on implementation practitioners (Albers, Metz, & Burke, 2020). Relating well to others is a real skill that not everyone has. Implementation science literature may highlight the need for ‘teamwork’ and ‘communication’ but, a bit like the bicycle example, relating is very different in practice than it is to it being written down on a piece of paper.

Whenever I am meeting with someone, whether a nurse, doctor, programme manager, researcher I will always be trying to relate with that person and develop good rapport. Relationships allow for learning and a two-way process of knowledge exchange. That exchange seems to go a lot better when the two people are able to relate well. Whether it is finding out the barriers and facilitators in a setting or evaluating implementation outcomes, implementation does not happen without relating.

Taking into account the advice and knowledge shared by Ioan Fazy, Laura Damschroder and Alison Metz, getting teams to engage in some kind of continual improvement and adaptation might be the way to go. Laura mentioned PDSA cycles. At the Improvement Academy we take a similar approach and call it Improvement Cycles.

These approaches stem from improvement science and train teams to respond and adapt to issues as they emerge in the setting. I think that these approaches which can be combined with implementation science may be part of the answer to the question ‘how to’ implement. If teams are trained and supported to get good at adapting interventions, these interventions will be less likely to fall prey to the constantly changing environment. Teams have traditionally been deterred from adapting interventions, because adaptation was seen as a bad thing, but that has begun to change.

To learn more about using improvement science techniques to help teams learn ‘hot to’ implement check out Part 3 of this blog series: Building on the old to make way for the new!

Contact for more information:

Kristian Hudson

Implementation Specialist at the Improvement Academy

Bradford Institute for Health Research

Kristian.hudson@yhia.nhs.uk

I work at the Improvement Academy in Yorkshire, England, UK. We are a team of implementation scientists, improvement scientists, patient safety experts and clinicians who work with frontline services, patients and the public to deliver real and lasting change. Check out our website at https://improvementacademy.org/