by Andria Hanbury

In this blog we walk you through an ongoing evaluation of a digital device being rolled out across the Yorkshire and Humber region for piloting. We will feed back on the findings in a later blog.

Digital devices in the NHS

The NHS Long Term Plan, published in January 2019, emphasised the importance of technology for the NHS. NHSX was then introduced, bringing together teams from the Department of Health and Social Care, and NHS England and NHS Improvement to facilitate digital transformation. NHSX will merge into NHS England and Improvement this year, aiming to further centralise digital transformation.

Colleagues from the Yorkshire and Humber Patient Safety Translation Research Centre are working on a number of projects focused on digital innovations, including developing and testing risk assessment scores and case finding tools, and an evaluation of the first Artificial Intelligence Centre in Europe, based at Bradford Royal Infirmary https://yhpstrc.org/research-themes-partners/digital-innovations-for-patient-safety/).

Examples of digital devices and digitally-enabled care that you may be familiar with include:

- Electronic prescription service

- Apps: self-management, exercise

- ‘Telemedicine’: phone and video consultations between patient and health professional in primary and secondary care

- Virtual wards: enabling patients to receive the care they need, at the place they call home via use of remote monitoring apps, medical devices and ‘wearables’

As a more concrete example, as a type 1 diabetic myself, I save so much time ordering my regular prescription online compared with dropping it off and picking it up in person, and my quality of life feels greatly improved through wearing an insulin pump. This delivers my insulin based on an algorithm linked to time of day and calculates my mealtime ‘booster’ doses based on how much carbohydrate I estimate for my meals. I can also share this data remotely with the diabetes care team, which we review together during a video consultation. There is less human error in my insulin dosing, fewer trips to the doctor and hospital and less waiting around.

The digital device that we are evaluating

TytoCare is a handheld, wireless, medical device. It can be used to perform medical examinations for the ear, throat, lungs, heart, skin, and abdomen. This enables specialists to monitor and review patients’ without the need for patients, or health professionals, to travel. The device was initially introduced during the first Covid-19 outbreak to reduce the risk of catching Covid-19 for vulnerable children who still required frequent medical input. There are two versions of the device:

- TytoHome device: examinations can be performed by a patient/carer, following simple instruction generated by the device. These examinations can be viewed remotely by a health care professional as part of a real-time consultation or recorded by the patient or carer and uploaded to a secure platform for later review by a health professional. An example of TytoHome in use would be a parent of a child with long standing respiratory problems using the device to listen to their child’s lungs, and then submitting the data for specialist review of lung function.

- The TytoPro device is used by health professionals to conduct medical examinations which can be viewed in real-time by another health professional (such as a specialist) or submitted and later reviewed. An example of the TytoPro device in use would be a district nurse using the device to monitor their patient’s temperature and heart rate and then submitting the data for review by a hospital consultant.

Thus, TytoCare enables remote monitoring of patient’s symptoms (e.g., as part of virtual wards and ‘hospital at home’ services), and the sharing of information from health professional to health professional. It reduces the need for patients to travel to appointments and provides the opportunity for collaborations between health care teams at different sites.

The evaluation

Background

The NHS England ‘Beneficial Changes Network’ (NHS England » About the Beneficial Changes Network) sought examples of innovations introduced in response to Covid-19. The call for examples accumulated in a shortlist of 700 digital innovations. TytoCare was one of these. Academic Health Science Networks across the country were asked to identify the most promising innovations, in their region, and pilot them regionally. The Yorkshire and Humber AHSN (YHAHSN) chose TytoCare based on its potential and based on the results of a small scale pilot already undertaken by the paediatric team at Bradford Teaching Hospital NHS Foundation Trust (TytoCare and Bradford Teaching Hospitals join forces in NHS ‘first’ – Bradford Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (bradfordhospitals.nhs.uk)).

Applied Research Collaborations (ARCS) have been asked to evaluate the pilots. Our Improvement Science theme is leading the TytoCare evaluation, working alongside the YHAHSN. We are supported by colleagues at the Improvement Academy who are contributing their implementation science expertise. And we are also working with the Health Economics, Evaluation and Equality theme (HEEE). This is a great opportunity for themes to work together, combining improvement science with health economics.

Sites participating

At the time of writing, there are 8 organisations and 13 different pilot projects spread across them, a further 3 organisations and 5 pilot projects hoping to launch imminently, and another 6 currently paused. These cover care homes (older adult and adult), adult acute care, paediatric acute care, urgent and emergency care, tertiary care (a cleft lip and palate service), and primary care. The devices are also being used in a variety of different ways (diagnosis, ‘hospital at home’ – monitoring of patients in their homes via different care teams – and virtual wards, which allow patients to get the care they need at home, rather than in hospital). Some sites are using home devices, some pro and some a mix of the two.

Improvement science approach to evaluation

‘Digital technologies bring many opportunities to improve people’s health and experiences of services but realising their potential will require investment and thoughtful implementation.’ (Kings Fund, position statement: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/projects/positions).

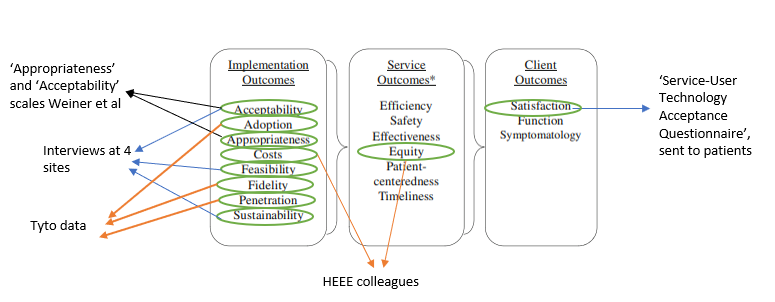

Our evaluation focuses on people’s perceptions of the device and the barriers and facilitators influencing their uptake of it. As such, we are gathering feedback from patients, health professionals, project managers and commissioners’ feedback via interviews at a sample of sites and validated surveys. We are also analysing data downloaded from the TytoCare device and some data collected and supplied by pilot sites (e.g., number of staff and patients trained). Through involvement of the HEEE theme, there will also be an assessment of intervention and implementation costs. We hope that the latter can build on some work examining the cost effectiveness of implementing innovations, which was initiated during the first round of the Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC) on the implementation science research programme led by Professor Carl Thompson: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26201387/. There is consensus that implementation efforts should ideally be guided by theory or a framework to ensure consideration of all issues (e.g., beyond ‘lack of time and money’ which people more readily site). There is also consensus that evaluation should be above and beyond assessing intervention effectiveness. This is an area of implementation research ripe for investigation, with a need to focus efforts on developing and testing validated measures of improvement and implementation science outcomes (the improvement science snapshot on an Implementation outcomes repository discusses this issue: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GXXpmRt5YeY). This is something that we hope to explore in the evaluation, enabling us to conduct a robust evaluation for the AHSN led pilot, but also enabling us to develop new knowledge regarding improvement and implementation science outcomes.

To guide our evaluation design, we chose two frameworks

1) Proctor et al’s implementation outcomes framework (2011). This has helped us to select our evaluation outcomes (see those circled in green), appreciating that some are not feasible to collect within the constraints of this project.

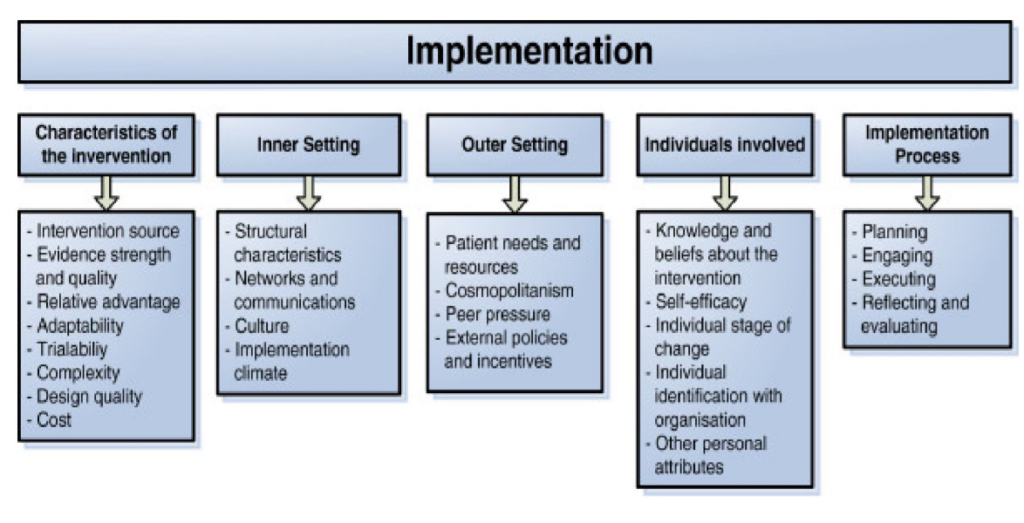

2) The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research by Damschroder et al (2009), to assess the factors that have helped or hindered implementation of the device from the perspective of the health professionals involved in the pilot. The 5 CFIR domains will be explored through a survey (free text items) and through the qualitative interviews, alongside some of the Proctor et al implementation outcomes. The Improvement Academy are collaborating with us to develop recommendations for how to optimise implementation of the device and other such digital devices, drawing particularly on the CFIR related findings.

Cutting the cloth

With approximately 9 months from start to finish for us to conduct the evaluation, measuring all of Proctor et al’s outcomes would be challenging. It would also mean significant burden for patients and health professionals, potentially being asked to complete multiple survey measures and/or to participate in interviews at multiple time points. As such, we have adopted a more pragmatic approach:

- Selecting a validated patient reported experience measure – The Service-User Technology Acceptance Questionnaire (SUTAQ) (Hirani et al, 2017). This was developed for telemedicine settings and is broad enough to use across all care settings.

- Focusing on implementation outcomes for which there are existing, validated measures available and combining these into a single feedback questionnaire for health professionals to complete. We are using Weiner et al’s (2017) Acceptability of Intervention Measure, and Intervention Appropriateness Measure. If we get a good response rate, we will run Rasch analysis on the data to assess the psychometric properties of the tools in a more stringent way, thus, contributing to the literature in this area.

- Piggy-backing CFIR free text questions into the health professional’s feedback questionnaire.

- Collaborating with a fellow cross-cutting theme, the HEEE theme, to benefit from their expertise to measure costs as per Proctor et al’s framework

- Making use of TytoCare collected data to measure some improvement outcomes (notably, adoption and penetration of the device within sites)

- Conducting targeted qualitative interviews at a small number of different sites and with a mix of different stakeholders, covering some of Proctor et al’s implementation outcomes and constructs from CFIR.

Gaining timely ethical approval, particularly capacity and capability sign off across multiple sites and ICs has been challenging, with trusts prioritising Covid trials over other health services research, and with care homes grappling with staffing. Nonetheless, we are enjoying collaborating with colleagues from different teams and organisations on this evaluation and contributing to the evidence-base around the introduction of digital devices. Our evaluation report will make recommendations regarding how to optimise device rollout and uptake, drawing on improvement and implementation science principles and insights.

The YHAHSN pilot of TytoCare is a finalist at the HSJ Partnership awards, 2022 for the category Most Effective Contribution to Clinical Redesign. We wish our AHSN colleagues the best of luck and congratulations on the nomination.