by Lynn McVey

Health and social care services in the UK rely, fundamentally, on the staff who offer, manage, and support them, whether that’s the catering staff who provide food and drink to patients, the social workers who protect vulnerable people, or the surgeons who perform life-saving operations. It’s essential that staff feel supported and valued as they carry out this work; as recent guidance says: ‘Staff can only care well if they feel cared for themselves’.1

But there’s evidence that health and social care staff don’t always feel cared for, despite some recent improvements. Less than half of healthcare staff are satisfied with the extent to which their organisations value their work, for example, and 29% often think about leaving their organisations.2 In adult social care, turnover rates are almost three times those of the wider economy3 and during the recent Covid-19 pandemic, care home staff talked about feeling undervalued, unrecognised and abandoned.4 Although pay, conditions and contractual issues are important here, workplace culture, communication and relationships are also key.3,4,5

This matters not just for staff themselves, but also for patients and service-users, given the well-established link between their safety and staff wellbeing.5,6,.7 Staff who aren’t well, for example, are more likely to make errors in the care they offer and the drivers of staff stress and burnout – such as insufficient staffing – affect servicer-users too. Caring for staff also makes financial sense: in healthcare alone, it’s estimated that savings of around £1 billion per year could be achieved by successfully tackling poor staff mental health and wellbeing and reducing people voluntarily leaving the NHS.8

This all means it’s of paramount importance to look after our health and social care staff. But how?

Understanding the problem. Much work is already being done to support staff wellbeing. The NHS, for example, spells out its commitment to improving the experience of all its employees in its People Promise, whilst many employers provide access to important wellbeing services such as counselling. However, support is often targeted at individuals rather than systemic issues that organisations themselves need to change, such as how incivility towards and between staff is addressed or how rotas are organised.5 Research shows that organisational-level interventions like these often have more impact than those aimed at individuals.5,8,9

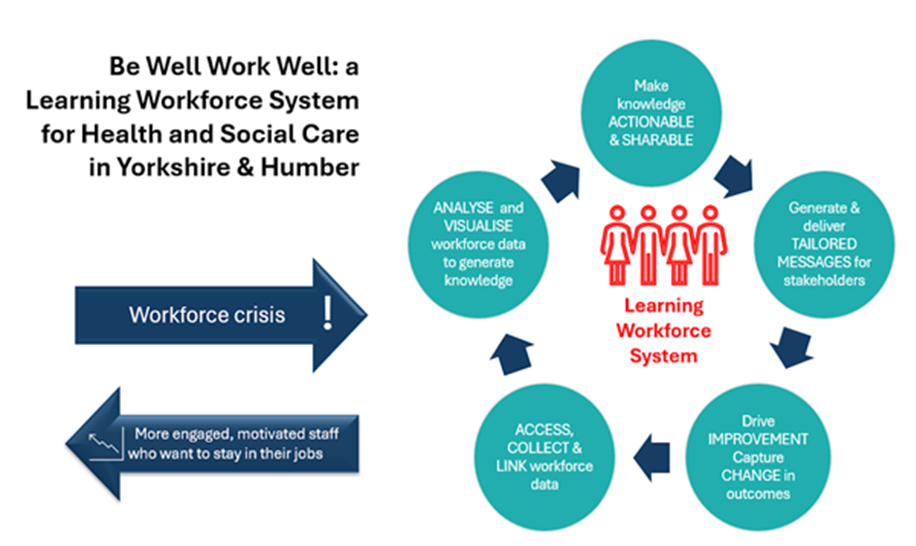

But even when organisations try to address staff wellbeing systemically, one size doesn’t fit all. So, a response or intervention that works in one place or for one group of staff doesn’t always work for others. It follows, then, that if interventions are to have real impact, we need to take local context into account. This is just what we plan to do in the Yorkshire and Humber region. Our proposed study – called Be Well Work Well – will use a learning health systems approach. Learning health systems are teams or groups that embed iterative, data-driven improvement into routine operations.10 In our system, which we call a ‘learning workforce system’ this will mean combining repeated cycles of data-driven improvement with robust evaluation to improve retention, experiences and outcomes for health and social care staff in the region.

With acknowledgements to the Centre for Digital Transformation of Health, University of Melbourne.

We’ll co-design our learning workforce system with health and social care staff and organisations, focusing initially on new starters in all roles. With consent, we’ll link these staff members’ de-identified staffing and health data with data from wellbeing surveys to provide powerful insights into the challenges they face. Then we’ll co-design evidence-based interventions that address those challenges, focusing on organisational solutions, and use the data to evaluate their impact.

Job demands and job resources. Our first task is to decide which data we need to collect. Here, we refer to one of the most well-established theories about staff burnout and stress, the Job Demands-Resources theory.11 JD-R proposes that all jobs comprise a mixture of demands (things that require sustained effort or skills, e.g. working long shifts) and resources (things that help employees manage demands and achieve goals, e.g. team cohesion). Engaged, motivated workers experience a balance between demands and resources, and this predicts whether they are likely to perform strongly and remain in their roles. However, there is little consensus about which job demands, resources and outcomes are important to study for health and social care staff.

To achieve consensus, we’ll be asking people who work in health or social care or who have academic or strategic expertise in workforce wellbeing and retention in the sectors to take part in up to three online questionnaires in what’s known as a Delphi process(approved by the University of Leeds’ School of Psychology Research Committee, 22 January 2025, ref. PSCETHS-1335). We’ll provide more information about this process, and an invitation to take part on our website in the next few weeks so watch this space!

Putting staff wellbeing at the heart of things. Staff wellbeing has long taken a back seat to caring for service-users, the core business, after all, of health and social care. But it’s increasingly clear that you can’t have one without the other; as a recent editorial in BMJ Quality and Safety says: ‘It is of paramount importance that a fully-staffed, psychologically well workforce is seen as ‘the’ foundational patient safety intervention across practice, policy and research going forward’.12 Our plans aim to strengthen that foundation.

References

- Maben J., Taylor, C., Jagosh, J., Carrieri, D., Briscoe, S., Klepacz, N., Mattick, K. 2023. Delivering healthcare: a complex balancing act: A guide to understanding and tackling psychological ill-health in nurses, midwives and paramedics. Guildford: University of Surrey. workforceresearchsurrey.health

- NHS Staff Survey. 2023. National Staff Survey 2023. [online] Available at: https://www.nhsstaffsurveys.com/Page/1056/Home/NHS-Staff-Survey-2023/

- Fenton, W., Polzin, G., Fleming, N., Fozzard, T., Price, R., Davison, S., Holloway, M., Liu, H., O’Gara, A. & Geddes. G. 2024. The state of the adult social care sector and workforce in England. Leeds: Skills for Care.

- Wilkinson, K, Lang, I, Thompson-Coon, J, Liabo, K, Goodwin, VA, Coxon, G, Cox, G, Marriott, C, Abel, C and Day, J. 2023. The Impact of a Public Health Crisis on the Well-Being of UK Senior Care Home Staff: A Qualitative Interview Study. Journal of Long-Term Care, pp. 338–349. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31389/jltc.154

- Maben, J. and Taylor, C., Jagosh, J., Carrieri, D., Briscoe, S., Klepacz, N., Mattick, K. 2024. Causes and solutions to workplace psychological ill-health for nurses, midwives and paramedics: the Care Under Pressure 2 realist review. Health Soc Care Deliv Res, 12(9). https://doi.org/10.3310/ TWDU4109

- West, M., Bailey, S., Williams, E. 2020. The Courage of Compassion: Supporting Nurses & Midwives to Deliver High-Quality Care. London: The King’s Fund.

- Hall, L.H., Johnson, J., Watt, I., Tsipa, A. and O’Connor, D.B., 2016. Healthcare staff wellbeing, burnout, and patient safety: a systematic review. PloS one, 11(7), p.e0159015.

- Daniels, K., Connolly, S., Woodard, R., van Stolk C., Patey, J., Fong, K., France, R., Vigurs, C., Herd, M. 2022. NHS staff wellbeing: Why investing in organisational and management practices makes business sense – A rapid evidence review and economic analysis. London: EPPI Centre, UCL Social Research Institute, University College London.

- Aust, B., Møller, J.L., Nordentoft, M., Frydendall, K.B., Bengtsen, E., Jensen, A.B., Garde, A.H., Kompier, M., Semmer, N., Rugulies, R. and Jaspers, S.Ø., 2023. How effective are organizational-level interventions in improving the psychosocial work environment, health, and retention of workers? A systematic overview of systematic reviews. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 49(5), p.315.

- Hardie, T., Horton, T. and Thornton-Lee, N., 2022. Developing learning health systems in the UK: priorities for action. London: The Health Foundation.

- Bakker, A.B. & Demerouti, E., 2007. The job demands‐resources model: State of the art. Journal of managerial psychology, 22(3), pp.309-328.

- Kirk, K. 2024. Time for a rebalance: psychological and emotional well-being in the healthcare workforce as the foundation for patient safety. BMJ Quality & Safety, 33 (8) 483-486; DOI: 10.1136/bmjqs-2024-017236.